Introduction

In this report I will go through some topics that define my investing process. I will also go through my two largest losses, and what I learned from them, as well as some of the pitfalls that I have fell into before.

What I will cover in this report are not rules as such since I think investing is an art and rules limit the flexibility and creativity of investing, at least in my case. What I will cover in this report are more like guidelines, and philosophical ideas that guide me towards what I think are good investments and trades.

Convexity or concavity

Convex and concave curves. math.stackexchange.

To put it simply there are two strategies in the world: convex and concave strategies. This can be applied to almost any field in life, including investing.

Starting with concave strategies, you can find these almost anywhere. Concave strategies are based on the idea of safe and almost certain returns. However, when these “safe” presumptions do not occur, you lose. Example in the world: thieves steal under the assumption that they will not get caught. This yields them consistent, safe returns. However, when they do get caught stealing, returns are 0 or even negative as they face the consequences of their actions. Example in investing: the simplest example are bonds, particularly US government bonds. In investing the term “risk free return” is often used to define the return of US bonds. These returns are considered secure and almost certain. However, were the US government to stop paying the interest on these bonds, returns would plummet.

Long Term Capital Management returns.

A firm that employed a concave strategy was Long Term Capital Management (LTCM). Had you invested $1 in 1994 when it was founded, you would have had $4 by 1998. However, in just 4 months it would have gone from $4 to $0.25 cents. They did a lot of arbitrage trading, which is also a concave strategy since the returns are almost guaranteed until something unexpected happens. The 1998 Russian financial crisis caused turmoil in the stock market, and it destroyed all the assumptions upon which LTCM based their trades on.

Convex strategies are those in which losses are often common at the beginning, in the hope of a long-term gain. An example of convexity outside investing could be the Theory of Evolution. Species evolve due to small changes in the birth of new creatures. Most changes (investments) involve no improvement whatsoever and therefore are “lost” (no returns). However, one small change (investment) can cause massive benefits (profits). As an example, the appearance of the thumb finger in prehistoric humans was one of probable millions of small changes or mutations that have appeared in evolution. Most of these millions of changes were of no evolutionary advantage, but the thumb finger meant a lot of benefits for early humans.

Theoretical returns of a venture capital fund. Jason D. Rowley.

An example of convexity in the investing world could be venture capital. In venture capital a lot of small investments are made in often very risky businesses and entrepreneurs. Most of these investments are expected to end in a complete loss of capital, in the hope that one or two of those investments end up being a home run. Examples of these early-stage investments could be early investments into Uber or Facebook, which probably made the bulk of the return in the venture capital funds which invested in them, while probably most other investments went to 0.

I have lived myself through a convexity strategy without even realizing it at the beginning. In 2017 and 2018 I invested all my money into uranium knowing fully well I was probably early in the cycle, and that there was going to be pain ahead of the road. I did this with the hope that 5 years from there, uranium prices would go back to more sensible prices, and my stock picks would perform exceptionally well. And indeed, I was correct, between 2017 and 2020 I lost nearly 50% of my money. However, by 2022 I had made over a 1000% average return on my portfolio.

To sum it up: I look for convexity in my portfolio. I search for opportunities that may lose in the short term, but with some certainty that in the future, the market will recognize the value of those investments. In 2017 I knew the uranium prices were going to recover, it was just a matter of when. Today I know that stocks like Manolete Partners or those in the platinum and palladium sectors will recover. It’s a matter of patience and continue buying even if prices decline, as long as the investment still makes sense.

My two largest mistakes

The two stocks in which I have lost the most money in relative terms are two Spanish stocks: Abengoa and Banco Popular. I was lucky enough that those losses occurred when I was 18 and 19 and I managed very little money. And in both cases my mistake was simple: buying into firms that had too much debt and were cheap for a reason.

In Abengoa I lost 100% of my money as it went bankrupt and in Banco Popular I lost 65% of my money. I am lucky to be very open minded, and therefore I sold all my Popular share before it went bankrupt, and the banking behemoth Santander bought it for 1 euro (yes, they bough an entire bank for 1 euro). I realized I was wrong about popular and decided to cut my losses.

The main lesson I learned from these mistakes, is that I needed to be very demanding with the balance sheet of the businesses I bought shares in. In fact, I knew I needed to have a very high level of accounting understanding, to evolve as an investor. That´s why I studied Accounting in university. And I was lucky enough that a lot of the courses I took involved understanding the principles of accounting, and how to fully understand each item in a financial statement.

The other lesson I learned was that it is okay to sell a stock at a loss. Many times, as investors we make mistakes, and when we do, the intelligent move is to cut the losses and move on. However, this is very tough as there are cognitive biases when investing as we will see later on.

Another large mistake I made was going big into exploration after I made a lot of money in uranium. I lost a bit of my profits made in uranium. After that I decided to select just a few exploration firms that I have shared in a previous report, and just put a small fraction of my capital into these stocks. I was lucky not to lose everything I had, which is the most common outcome in exploration.

Cognitive biases when investing

Anchoring bias: The anchoring bias is based on the thought that the price that we bought the stock at, or previous prices the stock has traded at have some profound meaning. As an example: Let’s say I bought shares in stock A for $10/share and the stock drops to $5/share. The anchoring bias will push me to hold the stock at least until the stock is above $10. Or to set another example with the same stock: say another investor bought shares at $10/share, and he assumes the stock will back up to its all-time high of $30/share. Even if the situation of the company worsens or even if he has made a mistake in his analysis, the investor won’t be willing to sell until the stock hits $30/share.

Temporality bias: This bias implies that we give a lot more importance to recent news and data than to older data. As an example: After the Chernobyl or Fukushima nuclear incidents happened, very few were considering investing in uranium or nuclear energy. But today we are witnessing somewhat of a nuclear renaissance. Circumstances haven’t changed much since then, except perhaps nuclear is slightly safer today than it was back then. But in the mind of investors, those incidents have a lot less importance today, as a lot of time has passed.

Magnitude bias: The size of events cause an unproportionate impact in our minds. Example: There are deaths occurring in coal mines on a weekly basis, sometimes daily, particularly in China. But very few news outlets cover these events. However, events like the Fukushima nuclear meltdown, cause major shocks among newsreaders, even though only one person died because of the nuclear meltdown. This causes investors to overreact to news that have very little real impact or importance. And this bias also causes investors to ignore certain realities (like how dangerous coal mining is in China) and therefore they don’t react at all.

Confirmation bias: Living in an echo chamber. We tend to accept data that confirms our views more easily than data that confronts our views. This makes us fall into an echo chamber in which we only listen to the “voices” that confirm the idea that we are right. Example: In the year 2000 it was evident that a lot of tech stocks were overpriced. However very few investors were able to see it as many investors were invested in such stocks, and any information they wanted to see would confirm the idea that tech stocks were fairly priced.

Emotional bias: A lot of investors create an emotional attachment with the stocks they buy. This is why I avoid using phrases like “I love this stock” or “I like this firm” because I think it unconsciously creates an emotional attachment to a stock. As Peter Lynch says: "Never fall in love with a stock; always have an open mind."

Loss aversion bias: It has been studied that losing money hurts multiple times more than the pleasure an investor gets from winning money. This makes us prone to allow losses to run wild and cut our profits quickly. Furthermore, this bias provokes two mistakes in investors: 1. It discourages investors from revaluating the stock since he may discover he is wrong, and the best outcome is to sell. The idea of selling at a loss is incredibly painful for most investors. 2. Since the bias discourages investors from reevaluating the stock, it also discourages us from buying a stock that may be falling for no logical reason. Sometimes the best returns are made when we buy a stock that is dropping heavily, because the sellers aren’t acting rationally.

Bandwagon effect: We sometimes feel more comfortable moving with the crowd than against it. When an investor sees fellow investors, or even neighbours make money on a particular type of stock, it causes the investor to copy that behaviour. As an example, tech stocks since the 2008 recession have outperformed most other firms in the stock market. This has pushed a lot of investors that probably have no idea of how tech firms make money into buying such stocks.

An analogy I like for this kind of behaviour is how many marine species form schools. They copy each other’s behaviours to form groups and thus avoid getting eaten by predators. However, many predators use this kind of behaviour to push fish into shallow areas, so they can feast on them. In the stock market similar things can happen. Short sellers look for overbought and trendy stocks that have bad fundamentals, in which put options are cheap and many are willing to lend stocks to short sell. This is done in order to corner the “fish” (bad investors) which are behaving in a herd kind of behaviour.

Narrative fallacy: Falling into trending or innovative stocks while avoiding more traditional but cheap stocks. This can be seen very easily nowadays. Quantumscape Corp for example is worth billions in the stock market, even though the company claims they may never turn a profit. While firms like Warrior Met Coal and other coal stocks trade for less than 8 times earnings. I am not advocating for coal stocks here. I am simply pointing out how innovative and trendy stocks trade at valuations that do not make sense, simply because there is a narrative behind them much stronger than in cheaper but more unpopular stocks.

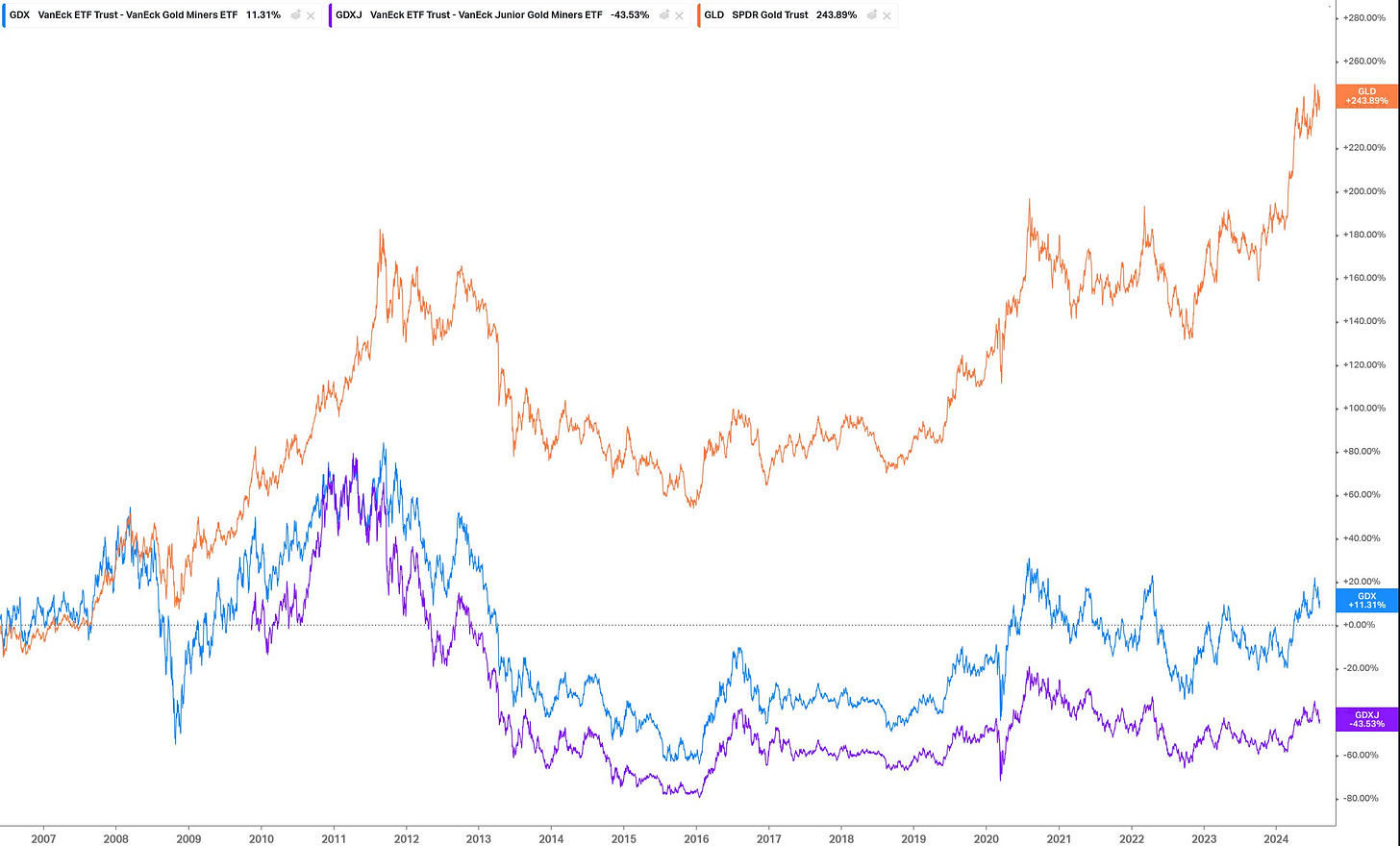

Correlation bias: Thinking that certain assets are always correlated and will continue to behave that way. Example: Many investors think that profits at gold miners always move with the gold price. However, gold prices have massively outperformed gold miners ETFs like the GDX and GDXJ.

Returns of gold vs gold miners. Koyfin.

Who are you buying your stocks from?

In the introduction I said that I believe investing is an art. And I consider that to be true. In a similar sense, I believe the stock market is a game. Even Warren Buffett considers it a game. And for me it’s a game about information, knowledge, patience and understanding.

Many years ago, I started to ask myself a simple question: Who am I buying this stock from? In other words, who is the seller? And even though this may seem like a simple question, I believe it lies deeply in the success you may have in the game of the stock market. In the game of the stock market the opponents are the sellers vs the buyers. And the determining question is often who has the most information? So, whenever you are buying the stock try to ask yourself: What are the chances I have more information than the person selling me the stock today?

As an example, according to NASDAQ´s website, there are 29 analyst firms covering Apple. That means there are at least 29 investors whose only focus is knowing how much Apple is really worth. Therefore, they have a lot of knowledge, understanding and information about Apple and I do not. As a result of this, I would never buy stock in Apple, as I know that chances are that I am being dealt the losing hand.

In the stocks I have in my portfolio, Ero Copper is the one with the most following and it has 9 analysts covering it. In the case of Generation Mining, it only has one analyst behind it. Therefore, chances are that in the stocks I buy I have more understanding of the stock than the person selling it to me.

When I was buying uranium stocks in the years 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020, there was almost no analyst coverage for the industry. And long-term investors in uranium stocks were tired of losing money, while the general stock market was rising. Therefore, after spending hundreds of hours researching uranium stocks, I knew that I was buying shares from people who did not know the stock well, or they were just fed up with the stock price action.

All this said, having more information than the person selling the stock to you will not guarantee a profit. In fact, between 2017 and 2020 I lost 50% of my money in uranium. Although by 2022 I had returned over 1000% average returns on my entire portfolio. However, buying into stocks that are unknown, hated or out of fashion after you have spent many hours researching the stock, is a good way to increase your chances of making a profit. This is simply because these kind of stocks do not have many analysts researching them, and very few investors are interested in them.

Margin of safety

When I was 19 years old, I read the book Margin of Safety: Risk-Averse Value Investing Strategies for the Thoughtful Investor by Seth Klarman. The book completely changed my thought process on how to approach investing. I learned that the investing game is not about finding stocks with huge upsides, since theoretically the upside is infinite in a stock (that is why call options have a theoretical infinite upside). The investing game is about finding stocks with very little downside. The reason I use upside in most of my valuations is not because I think the stock can rise 500% or 1000%, which it can, but because a very high upside potential often implies a very small downside potential.

Where to search for value opportunities:

Hated stocks: Warren Buffett said something along the line of “the intelligent investor doesn’t get much pleasure from being with the crowd, nor against it”. While this is true, hated, and unknown stocks tend to have much lower valuations since investors do not think rationally about them. Some good examples would be platinum group metal stocks and Manolete Partners today, or coal and uranium stocks before 2021.

That said, investors should be very careful with these kind of stocks as they are often cheap for a reason. Stocks like Intrum, Altisource or Dovalue, have returned horrible returns for shareholders in the past years even though they are hated stocks. The reason for the poor returns being that we are not yet in a recession, and these three stocks perform well in the worst of economic conditions.

Spin-off: Often excellent opportunities appear when large firms spinoff a segment of their business. This may be because firms that are spinoffs of other larger stocks suffer a lot of stock price drops. This often happens because investors want to be part of the larger firm, not the spinoff or because the spinoff is too small for a lot of investors, that have certain thresholds. Many institutional investors must be invested in stocks with large market caps, and they are forced to sell when the market cap goes down or they are given shares in spinoffs in which the market cap is small. And there are also occasions in which the large firm spins off a segment due to public relations reasons and ESG reasons.

As an example, in June 2021 Anglo American separated its core business from their thermal coal segment. Thus, Thungela Resources went onto trade in the stock market, separately from Anglo American. By September 2022, Thungela had gone up 1200% in the stock price (without even accounting for dividends). Anglo American sold its thermal coal business because it was out of favour in the market, meaning that investors hated coal stocks. This presented a great opportunity for investors to make a profit on the pernicious ESG standards, that have corrupted many businesses around the world.

Unknows stocks: Unknown stocks have little to no analyst coverage and most investors don’t follow them. Therefore, this area is ripe with good stock opportunities. A good place to start looking for these stocks is the OTC market, in which a lot of very small firms trade. A good example was the American Church Mortgage Company. In May 2022 the firm had a market cap of $2.1M and traded for $1.2/share. The firm had $1M in cash and $28M in a bond portfolio and mortgage loan receivables, while they had $21M in debt. The firm decided to liquidate all its assets and gave out a dividend of $2.8/share later that year.

An example today would be my top pick Manolete Partners. A firm that ticks the boxes both for unknown stocks and hated stocks. Manolete has £15M in net current assets (current assets minus total liabilities) and historically has delivered a 57% average gross margin, 23% operating margin and a 16% net margin. The firm buys makes a profit when they get involved in the insolvency of a firm, which makes a lot of investors hate Manolete as they profit from bankruptcies. This is a positive for me because that means that a lot of investors don’t think rationally about Manolete. Furthermore, the UK government banned bankruptcies for years during COVID, reducing the business volume and stock price of Manolete. This is when I decided to buy the stock as the price is at all-time lows. The icing on the cake is that the UK is now facing record high levels of insolvencies, thus providing a great catalyst and tail wind for Manolete.

Unusual structures: Institutional investors are sometimes wary of investing in stocks that have an L.P. structure or other less conventional structures. This is sometimes a great place to hunt for opportunities. For example, in Navios Maritime Partners LP I had over a 100% return as it was (and still is) trading for a massive discount to NAV. But when a friend pitched it to an institutional investor a couple of years ago, he said he would not invest in a L.P.

How I approach mining investments:

Looking for lows in the cycle: “In the natural resources space, the cure for low prices are low prices, and the cure for high prices are high prices” as Rick Rule rightfully says. This means that in most cases, unusually low prices in a commodity for a prolonged period often results in very high prices. This is because commodity producers eventually must decrease production due to low prices, which lowers supply and pushes the price of the commodity upwards.

Two good examples of catching commodities in the lows were coal and uranium in the stock market crash of 2020. The market for both commodities had been brutal for many years, and production was very low as prices didn’t incentive production. This caused a massive increase in coal and uranium prices after 2020.

A good example today may be platinum group metals. Palladium is down over 70% from its 2021 price peak. And the platinum price has been on a downward trend since 2008, the longest bear market I have ever seen for any commodity. This is unsustainable as both metals have a solid demand both today and in the foreseeable future. I plan on playing this idea the same way I played uranium: Buying into the best PGM project developers worldwide in the anticipation that prices will rise and developers have much more leverage to commodity prices than producers.

Good management: Mining is an incredibly tough business. Mineral deposits are getting more and more complex, while a lot of the mining techniques have not changed much in 100 years. Therefore, it is critical to find a good management team that knows how to build a mine and operate one. In mining there are three main stages: production, development of the mines and exploration.

In the production space a good example that comes to mind is Ero Copper, a firm whose management has built the company from scratch, creating one of the lowest costs producers of copper and gold worldwide.

In the development segment, Generation Mining is a good example. Kerry Knoll, the chairman of Generation has been chairman of Pine Point Mining (sold to Osisko Metals), CEO of Glencairn Gold (sold to B2 Gold), co-founder of Thompson Creek Metals (sold to Centerra) and Wheaton River Minerals (merged with Goldcorp). Therefore, he has a successful history of creating great assets which become targets of larger miners.

In the exploration stage, a good example is the management at Radius Gold: Simon Ridgway. He discovered Cerro Blanco (Bluestone Resources now) and one of the veins that ended up becoming Escobal (now owned by Pan American Silver). He founded Fortuna Silver and moved the company from CAD 0.17/share in the IPO in 2003, to CAD 9.73/share when he stepped down in February 2021. That is a 5,500%+ return.

Reasonable economic studies: A lot of economic studies have a 5% debt cost as input in the economic calculations. This is completely absurd as no bank would lend them money at 5%. I am not saying you should discard a firm that puts a 5% cost of capital in the economic study, but you should take with a grain of salt the NPV numbers they give you.

Firms should also put the number as post tax instead of pretax. Quite a few Australian firms I have analysed use pretax data, and I think this gives an erroneous idea of the economics of the project.

Good location: The aim of any investment in the commodity space is that the price of the commodity goes up, the management team increases production at lower costs, the firm finds a great deposit or that the firm develops a great deposit into a mine. Now, what is the point of achieving any of these goals if the location of the mine or deposit is in a terrible jurisdiction? I have seen great deposits in jurisdictions such as Liberia, but I have no interest in owning a project there as nationalization, or other issues may interrupt the mining process.

Red flags when eyeing mining stocks:

Management teams that lack experience or have a non-technical education background: Management teams that are led by people with little mining experience, or individuals that lack proper mining education are often a red flag. An exception to this rule would be Simon Ridgway who does not have a university degree. But often you should look for well-prepared professionals. An example would be David Cates (Denison Mines) who is an accountant. Another example is Wanjin Yang who is the CEO of Eastern Platinum but holds a job at three other different mining firms. Running a mining firm is hard enough, and I do not believe he can do a good job at doing four different jobs at four different mining firms.

Royalties sold on the main metal: When a firm sells a royalty on their flagship project, and that royalty is on the main metal of the deposit, it lowers significantly the profitability of the deposit. For example, McEwen Mining sold a gold royalty to EMX Royalties for 1% NSR on the gold of part of the Gold Bar Project. I think this transaction lowers a lot the profitability and gold leverage of that project.

An example of good decision making was the case of Generation Mining. Generation sold a royalty to Wheaton Precious Metals on all the gold and part of the platinum that Generation will produce. This was a great transaction because the project owned by Generation is mainly a palladium project. Therefore, it will not lower very much the profitability of the project, and it will not affect the leverage to palladium and copper prices of the project.

High compensation for management teams: Management compensation of mining firms, particularly those that have no revenue, like developers and explorers should be pretty low. In these cases, most of the money raised should go into development and exploration since those activities yield a return to shareholders. No company has ever gotten rich from paying a lot to executives.

A notorious example is Nexgen Energy, whose executive team gets paid a lot more than peers. Another less known example is Peter Marrone, who was the best paid mining CEO in Canada in 2014 even though Yamana was far from the largest mining firms back then. He is now CEO of Allied Gold. A counter example is Radius Gold, which spent almost 10 times more in exploration than in salaries and benefits in 2023. This is the kind of behaviours I like in firms: They spend money in activities which are accretive to shareholders.

Not spending most of the money on the project: This may sound like an obvious one, but a lot of development and exploration companies do not spend a lot of money in development and exploration. Nexgen for example spent C$109M in 2023 in exploration and evaluation assets while they spent C$83M in share-based compensation, salaries, office, administrative, travel and professional fees. This does not look good on a mining firm with no revenues. Another example: Uranium Energy Corp spent more on general and administrative expenses than on mineral property expenditures in 2023.

Owning stock in the firm: Management should have “skin in the game”, meaning they should own shares in the firm they manage. After all, it is great to make your shareholders rich, but it is even better if you get rich along them. But beware of the price they bought the stock at. Some management teams will issue the stock pre-IPO at $1 cent per share to themselves, and then float the IPO at $1 per share. I like to see the management team buying shares in the open market, and/or buying shares in the private placements.

Beware of which company the firm contracts for projects: Some firms will hire companies owned by management to carry out projects. I recall years ago analysing Eastern Platinum, only to find out that the firm had hired a contractor owned partially by employees to construct the chrome production (recycling) plant. I have no problem with these kinds of transactions if they do a good job. But I do not think they look good on management.

Low quality economic reports and resource studies: I will do this one in a separate section as it is a lengthy subject.

Choose the company, not the narrative

When I started investing in uranium in 2017 and 2018 there were between 70 and 80 uranium related firms in the world. And I went one by one studying the company and its management. In this sense I did a very similar thing in the blog with platinum, palladium, and gold companies. Back then I chose around 8 or 10 uranium firms, and I put all my money into them. By 2020 there were less than 50 uranium firms in the world, some of them had gone broke and others had changed their business. Incredibly enough not one of my 10 uranium stocks had gone broke, albeit ALX did change its name from ALX Uranium to ALX Resources. However, ALX kept all its uranium assets intact.

What I learned from this experience was that the narrative and the fundamentals of a commodity are very important. But even more important is choosing the right firm to play the narrative. Jose Ruiz de Alda, one of my teachers in grad school and one of the partners at CIMA Capital, once told us in a class: “There is nothing sadder in investing, than choosing the right moment to invest in a commodity cycle but choosing the wrong company.” I think its key to choose the right company when investing into metals.

I try to choose the right company by following all the parameters I mentioned before: good management, the firm has a good economic study, the firm still owns the royalties on its main metal, its assets are in a good location, management compensation is fair, and the firm is spending the money to develop the asset, not to enrich the management team with the shareholder´s money.

Valuation

When it comes to developers its very practical to compare them to peers, particularly in more niche metals like PGMs or uranium, where comparisons are easier since there are fewer players in the industry.

Once you have data to compare each company against another, you can go into the finer details that I mention in this report.

With producers the task of valuation is tougher in my opinion. Managing a producing mine is almost rocket science and the probabilities of something going wrong are relatively high. Just search in google for “mine accidents” and you will get a grasp of what I am talking about. As an example, Victoria Gold stock price is down over 90% in a few months after an incident at their Eagle Gold Mine.

With producers you must consider: Their current and historical margins, the quality of management, the current and historical grade of their mines, balance sheet, metallurgy, jurisdiction, royalty expenses, and the pipeline of projects they have to keep the company alive, just to name a few important data points.

For their valuation you can use PE multiple and/or DCF (please use a high discount rate as miners don’t get cheap debt).

What to look for in an economic study or resource study and red flags in them:

The obvious:

1. High IRR post tax

2. High NPV post tax relative to CAPEX numbers

High level of metal recoveries is very important. Look for nearby mines or mines with similar geology to understand the metallurgy better.

Be careful with reports that try to spread real capital costs out, often common in long life, low output mine plans.

Watch out for how thin they grind the ore to test for metallurgy. They sometimes grind it so thin that it delivers excellent metallurgical results in the report, but in practice they would never grind it that thin in a real mine.

Check out the firm who is writing the economic report or the resource study. You may find that they have done excellent work before or perhaps very bad work.

In resource studies be careful with the individual deposits that they take into account for the global resource. These deposits are sometimes far apart and/or have different metallurgies and would not be economical bringing them together into production.

Watch out for equivalent ounces or pounds. Example: This deposit has 2 g/t Aueq, meaning the grade is equivalent to 2 grams per tonne of gold, taking all the metals into account. Sometimes different techniques must be used to extract different metals in a deposit. So do not always use equivalent terms when measuring the size of a deposit, always separate each metal.

Personality traits of a good investor:

For this section I will limit myself to quote Warren Buffett.

At a speech he said: “I look for three things when hiring people: intelligence, initiative and integrity, and if he does not have the latter, the first two will kill you.” He has also mentioned several times that he looks for people with stable personalities, more specifically: “A person with a personality that does not derive great pleasure for being against the crowd nor with it.” I might add that I recall him saying that patience is very important in this business, but I may be wrong.

What I like about his approach is that this personality traits are achievable in life, you can work on yourself and do introspection to achieve them. The only one perhaps not achievable is intelligence, but Buffett has said himself that you do not need a very high IQ to achieve what he has achieved.

Forensic Accounting in your analysis

I think that reading through annual reports and particularly the notes of the financial statement will put investors ahead of the crowd. But having a deep understanding of each accounting item is also crucial. To this extent I think accounting knowledge is key to move ahead in this game.

I will not go into much detail in this section as the report is already over 20 pages long. But once you read a few hundred financial statements will start to notice things that are not right, like lack of details in the notes of the financial statements or too many details (which is also a red flag). This may seem contradictory, but I will set an example: I remember being taught about the Olympus accounting fraud in grad school, and the income statement had an unusual amount of detail. An amount of detail that you can commonly see in a note, but not on the actual income statement. Turns out the company was doing this in purpose to avoid any suspicion of fraud.

Due to the large losses I have suffered due to the company I invested in having too much debt, I am particularly focused on the liabilities side of the balance sheet. I think everyone should check the terms of the long-term debt as sometimes debt repayments are closer than one my think, or interest payments are very high.

I like to see large accounts payable if the company needs them, mostly because it is often interest free debt. Suppliers know the company better than I do, and if they trust the company enough to be in debt with them, I think that is a good sign. That said there is also accounts payable fraud out there. So, try to check for unusual pricing or unfamiliar vendors (just to name a few) if you suspect of an accounts payable item.

Circle of competence

Circle of competence is the area of expertise in which you feel comfortable enough, that you can understand the dynamics of a company, or industry if you were to invest in them.

In my case my circle of competence is mostly mining, litigation (like Manolete Partners or Litigation Capital Management), deep value (when the company trades well below its liquidation value or book value) and I am in the midst of understanding the oil and shipping industries. However, I am generally very happy investing in a company engaged in a different industry, if it is cheap and there is a catalyst or tailwind, something I consider critical in my investing approach.

A tailwind can have many forms. For example, let’s take Manolete Partners. The UK banned insolvencies for a few years, which made the stock price plummet, which created an interesting situation from a valuation standpoint. Now Manolete is trading at near all-time lows in the stock market. However, insolvencies in the UK are at all-time highs, which is a major tailwind for Manolete´s business which relies on a constant flow of insolvencies. In fact, Manolete makes money both in good times and bad times, due to the fact that there are always insolvencies. Manolete fits perfectly into my investment style: It has a good balance sheet, good management, it’s a business that makes money all along the economic cycle, it has a tailwind to favour it, it’s very unknown and it’s in a somewhat hated industry, therefore investors do not think rationally about it.

Absolute returns vs relative returns

I think an investor should compare its returns against the ones he achieved the year or years prior to that moment, not against an index. As investors we should aim at constant improvement and betterment. Therefore, comparing ourselves against the average return in the market does not make a lot of sense to me.

Something I really like about the businesses I invest in, is that I want them to make money regardless of the circumstances. When I look at a business I like to think: It is just a matter of time I make money with this stock, not a matter of “if this or that happens” but a matter of “when”. If you look at my top picks like Manolete Partners, Ero Copper, A-Mark Precious Metals, platinum group metals or Mongolia Growth Group, it is very certain they will rise in price, I just do not know when. This is why my investment horizon is at least 5 years.

I know that Manolete Partners will profit from record high insolvencies in the UK, it’s just a matter of time. I know Ero Copper will profit from its low cost of production and Ero doubling output this year, I just do not know when it will happen. I know PGMs will go back to more reasonable prices, I just do not know when. And I know that uranium prices will continue to rise, I just do not know when. Sorry to sound repetitive but I wanted to make the point very clear: I am very patient and I am more than willing to see a stock pick go down in price as long as the thesis is still solid. From where I stand, it is just a matter of time these stock picks appreciate in price, and I am more than willing to wait.

Of course I could be wrong in my stock picks. And that is why I am always researching more into them. If I find out I am wrong or if management does something which does not make sense to me, I will be a seller.

Conclusion

I hope I have not bored you with this report. This is a report I was looking forward to as it helps me think more clearly about my investment process. In fact, it only took me a couple of days to write the report. Hopefully some of you will see flaws in my investment process so I can improve it, if you do, please let me know. I am always looking forward to learning more. Otherwise, I hope some of you find it insightful.

Any feedback is more than welcome in the comments, or you can send me a message on Substack or through my twitter (X) account @AAGresearch.

As always, I want to thank my girlfriend Yeimy, who has helped me a lot while I was writing this by myself. This report and this blog would not be possible without her. Thank you.

I hope this finds you well,

Alberto Álvarez González.

Gracias

Vaya pasada de post Alberto, muchas gracias por aportar tanto de manera desinteresada a la comunidad, eres un ejemplo para muchos. Un afectuoso saludo