Summary

· In this report I will explain the price mechanism of currencies and their history. I will assume a free-floating exchange rate system.

· Today we count with the help of David Sanz, he is a professor at the Catholic University of Ávila and Omma Business School. At Omma he was my history teacher while I did my master’s degree in Value Investing and Austrian School Economics. Although I have written this paper, he has revised me and advised me as to how to improve it. I thank him for it.

Introduction

This report can be considered a continuation of my report on gold: Gold: The return to a 2000-year-old trend. For those that have not read it, I explained in that report how gold is the closest instrument there is in the world to “Perfect Money” as explained by John Forbes Nash Jr. Nash was the inspiration for the movie A Beautiful Mind, which I highly recommend.

No fiat currency in history has lasted more than 100 years, and I do not think the current fiat currencies will be any different. Considering most of the world uses fiat currencies I believe it is appropriate to write a report on how fiat currencies work and why they fail.

What is a fiat currency?

The word fiat comes from the Latin word fieri, a verb that could be translated into “to become.” Therefore, the term is very self-explanatory, it means the government forces a certain instrument to become a currency. I use the term currency because banknotes are not money in the strict sense of the word. Money is not imposed as a top-down approach in society, it is always bottom-up.

This said, when the quality of a fiat currency is high, society will embrace it in a bottom-up approach. The perfect example of this is the US dollar. Panama, Ecuador, El Salvador or East Timor are examples of countries in which the dollar is legal tender. In other countries like Costa Rica or Honduras the dollar is commonly accepted. The US government didn’t force its use in these countries. But the quality of the dollar is superior to their prior currencies.

There is also a religious connotation to the term fiat. In the Bible in Luke 1:26-38, the word fiat is mentioned. In Latin it says: “Ecce ancilla Domini; fiat mihi secundum verbum tuum.” The version in English is translated into: “I am the Lord’s servant. May your word to me be fulfilled.” However, I prefer the Spanish version as it is more literal: "He aquí la esclava del Señor; hágase en mí según tu palabra". “Hágase” can be translated more precisely into the verb fieri or “do” in English.

Most of the currency households own nowadays is in the form of a deposit in the bank. But banks hold those deposits as current liabilities in their balance sheet. Therefore, bank deposits are not money nor deposits, but bonds with which we finance the banks. And even if we hold the banknotes at home, you will notice those euros or dollars are signed or stamped by the central bank as those notes are debt issued by the central bank itself. Therefore, banknotes are bonds that the banks owe to the holders of those bonds (banknotes).

As a result of this, we should consider banknotes a substitute for money, not money.

What is the demand and supply of a fiat currency?

One of the most misunderstood concepts in terms of currencies is the demand and supply. And it makes sense, because most people might think that purchasing a good with a currency might mean we are demanding the currency. This is not the case.

Simply put in an example: The demand for a fiat currency is a household or government buying that currency and holding it. If I were to exchange my euros for dollars and keep them in a bank account or in my house, that would increase demand for dollars. However, if I were to exchange those dollars for gold, I would increase the demand for gold and decrease the demand for dollars.

M*V = P*Q, relates to the quantity theory of money. In this equation, M represents the supply of money, V represents the velocity of money, P represents the price level, and Q is real output.

The velocity of money measures the number of times that one unit of currency is used to purchase goods and services within a given period. And velocity of money is often correlated with inflation rates, as the users of that currency rush to exchange their currency for other goods as they expect inflation to rise. In fact, from the paragraph above, you can easily see how velocity and supply of money make inflation rise.

Supply of a currency is the amount that is printed or digitally created by any given entity. And I say any given entity because as Professor Richard Werner has explained, money is also created whenever a bank gives out a loan. Therefore, although central banks are responsible for a lot of the currency created, private banks also play a role in this system.

How do fiat currencies derive its value?

Inflation is the destruction of purchasing power of any given currency. As an example, in year 1 you can buy 100 units of goods with X amount of currency, and in year 2 you can only buy 90 units of those exact same goods with that X amount of money. That means you have lost purchasing power and therefore your money has lost value. That is inflation.

So, if inflation is the destruction of currency value, the lack of inflation is the appreciation of the value of said currency. This is called deflation, and it means that you can buy more goods with the same amount of currency you had.

Therefore, inflation dictates the value of a currency, so we ought to explore the phenomenon of inflation. And that is rather simple at first since there is only one factor that determines inflation: Inflation expectations. That's it. Since fiat currencies are the result of government laws, and the willingness of taxpayers to pay their dues to the government, the value of these currencies is primarily subjective.

As a result of this, inflation expectations are the critical element that central bankers are often obsessed with. This is primarily due to the vicious cycle a currency can go into if inflation expectations run out of control. If economic agents have high inflation expectations, velocity of money will increase, increasing inflation and increasing inflation expectations. It is exceedingly difficult to break this cycle.

With all these arguments I am not trying to defend that a government can print as much as they want without affecting inflation. I am arguing that as long as demand outstrips supply, inflation will remain under control. However, this is a dangerous game as demand for a currency can fluctuate. Furthermore, if a government were to print too much currency, this can affect demand for the currency and inflation expectations. But the boundary between too much printing and just enough is not clear. And therefore, governments ought to be careful with how much currency they print.

Finally, it is worth noting that power is the key factor that drives inflation expectations in a fiat currency. As long as the issuer has power, their minting power will remain strong.

Pound Dollar Exchange Rate (GBP USD). Measuringworth & Macrotrends.

A fitting example of this last paragraph is the decline in value of the British pound versus the US dollar. In 1931 Britain left the gold standard. However, in the first decades of the 20th century we see a lot of fluctuation in the pound, as WWI hits Europe and the US shows its resilience. But WWII and the independence in 1947 of Pakistan and India, followed by others like Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Libya, or Israel (British mandate) proved the UK no longer ruled over the seas. Its power had been diminished.

Case study 1: The US after the 2008 financial crisis

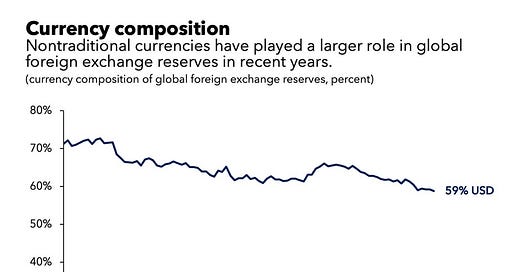

M1 money supply. FRED.

M1 is a measure of the money supply that includes currency, demand deposits, and other liquid deposits, including savings deposits. From 2011 to 2018 the money supply in the US as measured in terms of M1 effectively doubled. However, inflation rates in the US ranged from 0.70% to 3% per year during this period.

Gold and DXY index. Koyfin.

Furthermore, during this period, the US Dollar appreciated against other currencies and gold prices went down a bit. The U.S. Dollar Index (DXY) is an index (or measure) of the value of the United States dollar relative to a basket of foreign currencies. And gold can be seen as a proxy to measure how much purchasing power the US Dollar has lost: The more the gold price increases, the less gold you can buy with your dollars.

I chose gold prices and the DXY as proxies to measure the strength of the US dollar. But other commodities had a similar performance during this period.

Therefore, by any measure that we can imagine the dollar maintained its value or even increased it while the money supply doubled. This can be contradictory for most people as we often assume that there is an inverse relationship between the amount of currency printed, and the value of said currency.

But how can this happen, one could ask himself. For an answer, I refer you to the explanation of demand versus supply I mentioned on the previous section. The money supply doubled over this period, but if economic agents (any actor of the economy) are demanding even more dollars than what is being created, then the price of the dollar will increase relative to other currencies and commodities.

And the only reason that people demand the dollar is because there is trust in the “fieri” of the US government. In other words, economic agents trust the ability of the US government to force the use of the dollar. As long as that trust remains intact, there will be demand for dollars, as economic agents keep holding that currency.

Case study 2: The US in the 1970s

In 1973 US president Nixon stopped the convertibility of the dollar to gold. This was the result of lost trust in the government of the US.

From 1959 to 1971 the M1 money supply had increased by 50%, but the gold that was backing the convertibility had not increased. In fact, the gold held by the government had decreased.

The holders of US government bonds began converting their bonds into dollars and after that exchanging the dollars for gold. And the US government was forced to stop the convertibility of dollars to gold.

Economic agents were witnessing this and their trust in the US dollar was eroded, pushing inflation to 8.70% in 1973 and 12.30% in 1974. In response, the Federal Reserve pushed interest rates to 9%, which provided the economic agents with the tranquility they needed: The Fed was willing to do what was necessary to keep the value of the dollar.

By 1975 inflation had dropped to 6.90% and to 4.9% in 1976. But in the middle of 1975, something unexpected happened: The US lost the Vietnam War. This may seem trivial to us today, but the US was the undisputed world power back then. The fact that they had lost a war in a remote region of Asia to the guerrilla and Chinese communists meant something had changed.

The lost war was a brutal blow to the trust in the US government. And by 1979 inflation had exploded to 13.30% even though interest rates had climbed to 12%. Paul Volcker had to push interest rates to 18% to push the economy into a recession, so economic agents would demand more dollars by holding them. In a recession economic agents will want to hold onto a currency they trust in case things get uglier. This raised demand for US dollars.

With this example I want to prove to you that interest rates can go up to double digits like in 1979. But if the people have lost faith in the ability of the government that has imposed a fiat currency, there is almost no turning back.

Side note: A more recent example could be Argentina. Until recently they had triple digit interest rates, but their currency was devastated. If people do not trust you, no matter how high you push interest rates, the currency will not recover.

Case study 3: German hyperinflation after WWI

When I studied German hyperinflation in history class in school, the teacher taught us how the government had printed too much money. But my teacher put little emphasis on the fact that Germany lost WWI.

In fact, during WWI, England printed a lot more money than Germany did. But this did not cause hyperinflation for England, although they did have double digit inflation rates for most of the war. Furthermore, after the Treaty of Versailles was signed, England went into deflation for almost a decade.

The Economist, 1924. Millions.

The reason I am explaining this case study is that this proves how inflation rates are not dictated by the amount of the currency being printed, but by subjectivity and how that impacts inflation expectations.

Germany had lost the war and was humiliated in the Treaty of Versailles. Economic agents knew Germany could not be trusted to back the currency, and that the debt to other European powers was enormous. At this loss of trust, agents started dumping marks to buy anything at sight and exchanging it for other currencies.

I hope I have made my point clear. Trust is the critical part of the equation to value a fiat currency and there lies its weakness: For how long can a government hold this trust? One can only wonder which inflection point will push to euro or the dollar into hyperinflation. I do not know it and I believe its impossible to know, but I have the certainty that it will happen. However, this inflection point could happen in 1, 10 or 100 years. There is no way of knowing.

A note on cryptocurrencies

On my report about gold, I explained the main advantages gold has versus cryptocurrencies and more specifically versus Bitcoin, so I will not get into much detail here.

However, I would like to propose a thought exercise. In a conference Warren Buffett explained that 100 years ago there were thousands of car companies in the US. Had you known that in the 21st century cars would dominate the transport industry, you may have been tempted to pour all your money into automotive stocks. That would have ended badly. Ford and Tesla are the only car companies that have not gone bankrupt in the US.

According to Statista, there are around 10,000 cryptocurrencies worldwide. Therefore, even if we knew that 100 years from now all trade will be done in cryptocurrencies, it would be next to impossible to know which ones will succeed and which ones will fail.

If the example of the car industry proves to be right, chances are the over 99% of these coins will fail. With perhaps a handful of them having some actual utility 100 years from now.

As a result of this, I much rather watch the crypto market from the sidelines and wait for the market to do what is does best: Evolve and let the fittest survive. Once the cleansing is done, I will happily reexamine the market.

One could argue that Bitcoin has the first mover advantage. Some people may equate Bitcoin to Ford. But that would be a mistake. Pioneers like Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot or Robert Anderson invented vehicles in the 18th and 19th century respectively. But neither got far. I would argue that the first mover advantage is grossly overvalued.

Previous fiat systems and why they failed

In this section I will examine the main attempts to use paper money. I will avoid including some anecdotical attempts such as those during wartimes. Examples of this would be the Spanish attempt to introduce paper money during the Granada War between 1482 and 1492, or the 1683 attempt by the Bank of Amsterdam to do a fiat currency.

1. China´s first attempts: In China we have the first examples of a fiat currency in between the 7th and 13th century AD.

In the 10th century AD, the Song Dynasty issued the first paper money. Theoretically it was backed by silk, silver, and gold but convertibility was impossible.

However, as users of the currency were used to physical commodities being used for money, adoption was difficult. And the Emperors kept printing more paper. The government tried to force its use by making people pay their taxes with paper money, but these efforts failed as people lost trust.

But it was not just the government printing more currency what caused its debacle. In 1209 the Mongols started their invasion of China. And this was the final nail in the coffin.

2. Mongols: After the Mongol invasion of China, Kublai Khan established a paper currency of its own in the year 1260. It had some success as it was first convertible into silk and later it was convertible into silver. By 1350 the notes were not convertible into anything and failed miserably with hyperinflation.

3. Persia: In 1294 Gaykhatu, the ruler of one of the Mongol southern regions of Ilkhanate (Today´s Iran) introduced a paper money. However he quickly lost the trust of the users, the currency failed, and Gaykhatu was assassinated.

4. Sweden: In the 17th and 18th century some attempts to introduce a fiat currency were made. But in the first attempt Johan Palmstruch (the inventor of the currency) was sentenced to life in prison. Palmstruch through the creation of the Stockholms Banco started issuing paper money in 1661. But the bank started giving out too many loans and was liquidated in 1667.

Throughout the next century Sweden attempted other fiat currencies with no success. In 1776 they went into a silver standard.

5. New France: In the 17th and 18th century New France was facing a shortage of gold and silver. This forced the local authorities to create paper money. This was a success, and it lasted almost 80 years. However, after the Seven Years' War and the Treaty of Paris (1763), France gave most of these territories to Britain. This forced the French government to turn the paper money from New France into debt issued by France. However, the French were bankrupt and by 1771 this paper money (or IOUs) was worthless.

6. France: During the prerevolution and revolutionary periods of France, a currency called Assignats was created. In 1790, 400,000 livres' worth of assignats were created. A 5% interest was paid on the holders of the assignats. This interest was paid thanks to properties confiscated during the French Revolution from the Catholic Church, the monarchy, émigrés, and suspected counterrevolutionaries for "the good of the nation".

Later that year the interest payments were abolished and a further 800 million units were issued. By 1796 the issues had reached 45.5 billion francs, and the value of the currency collapsed.

7. Spain: During the Spanish Civil War (1936 – Apr 1, 1939) each side of the war printed its own currency. Most of this currency was paper money. The fascist side of the war had little access to precious metals. And the republican side decided to sell 510 tonnes of gold (72% of the national reserve) to Joseph Stalin in exchange for their military support. After the war, the money printed by the Spanish government (Republicans or communists) had no utility under the new regime of Franco. This paper money faced hyperinflation and disappeared.

Conclusion

I do not think any current fiat currencies will go back to a gold or silver standard. I do not believe either that a concept like the bancor is realistic nowadays. The bancor was a supranational currency that John Maynard Keynes and E. F. Schumacher proposed. It was based on the idea that a currency could be backed by a series of commodities.

The main reason I believe this to be true is because no central bank or president is incentivized to back their currency with anything. Doing so would limit their own power.

However, gold and silver will continue to have strong demand, both from monetary and non-monetary sources of demand. And I believe both will serve as strongholds for those of us worried about the declining value of fiat currencies in general.

The value of fiat currencies is linked to the credibility and stability of a country. So how long will the dollar last? It can last a thousand years, provided that the US government is stable all that time.

Although it is true that no fiat currency has lasted for more than 100 years or so, I believe the US dollar will continue being a demanded currency. The reason being that the US holds the most powerful and dynamic economy. They also have the largest military in the world. Therefore, their power is unquestioned.

China is facing a demographic cliff. The European Union faces zero economic growth and political uncertainties. And India´s GDP per capita is 95% lower than the one of the US. Therefore, I cannot think of any country that can substitute the US as the issuer of the most used currency.

In conclusion, I believe the US dollar will probably face a similar fate than the Spanish dollar, also known as the piece of eight. The Spanish dollar was the most used currency in the world from the 16th century until the early 19th century. Its decline was very slow, and I believe that will probably happen to the US dollar. Therefore, we can rest assured that the US dollar will continue to have purchasing power for quite some time. To quote the great investor Rick Rule: “The US dollar is the prettiest pig in the slaughterhouse”. Every fiat currency is going to get slaughtered. But I believe the US dollar will be the last.

“How did you go bankrupt?"

“Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

Ernest Hemingway

Any feedback is more than welcome in the comments, or you can send me a message on Substack, or through my Twitter (X) account @AAGresearch.

As always, I want to thank my girlfriend Yeimy, who has helped me a lot while I was writing this by myself. This report and this blog would not be possible without her. Thank you.

I hope this finds you well,

Alberto Álvarez González.

Disclaimer: I assume no liability for any and all of your actions, whether derived out of or in connection with this information or elsewhere, and you hereby warrant and represent that any and all actions that you take or that you may take at a later date in connection with this information shall remain your sole responsibility and, in case, I shall not be held liable for any such actions.

Excelente, apasionante, esclarecedor. (Excellent, exciting, enlightening)

GRACIAS!

Excelente artículo. Gracias por compartir.